The Kuntanawa Tribe

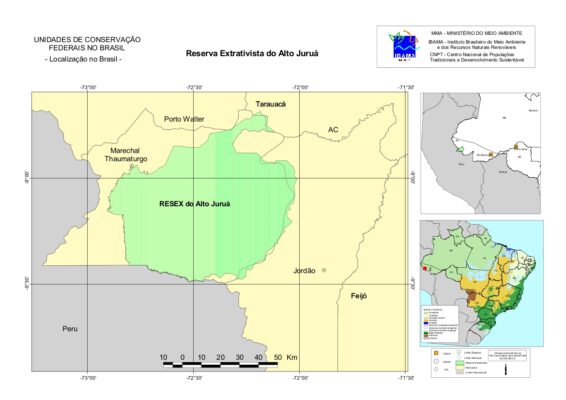

The Kuntanawa were reportedly wiped out due to the violent targeting of indigenous peoples during the rubber plantings that were incorporated in Acre between the late 19th and early 20th centuries known as raids. The last known descendants of this society are part of a large family, previously referred to as “the caboclos of Milton” in association with their forebear’s name (Milton Gomes de Conceição). This ethnic origin has since been embraced, leading to a strong sense of indianity. It is backed by their lineage and exclusive history: the recent endeavours to create and uphold the Alto Juruá Extractive Reserve; dealings with nearby native peoples; reviving ceremonies involving ayahuasca and Kuntanawa rapé; in addition to feeling the effects of racial and political discrimination.

The name

The ethnonym was originally written Kontanawa, which means “coconut people”. This is also how government documents and the press refer to them.

The name Kontanawa, or Contanaua, is the most frequently cited (Tastevin, 1925 and 1926, Macedo, 1988, Aquino and Iglesias, 1994) in bibliographical references.

Ayahusaca

Since the 1960s, Tejo rubber tappers have been aware of ayahuasca as a result of neighbouring indigenous cultures. However, it was not until the late 1990s that Milton and his sons had their first encounter with the ancestral beverage. The stories of Dona Regina had new meaning in this context and it reinforced the strong ethnic identity between the “caboclos de Milton” group emotionally and positively. Subsequently, they had more significant contact with the ancient drink after they took part in two trips. In 1989, they joined singer Milton Nascimento to Kampa Indigenous Land near the Reserve area. Two years later, members from their group were part of survey teams to register people from the Reserve who traveled by high river Tagus commanded by Antonio Alves and Terri Aquino.

During those trips, they encountered renowned pajés and attended ayahuasca sessions with them. Afterward some of Milton’s sons started to make preparations for ritualistic consumption of ayahuasca and conducted ceremonies with it regularly.

Furthermore, shamanic meetings involving representatives from neighboring Indigenous Lands began to take place at rubber tapper assemblies since 1989; one night was always predetermined for those who wanted to experience ayahuasca under shamans such as David Lopes Kampa.

Kuntanawa Rapé Snuff

Through the contact with neighbouring tribes they also got introduced to Rapé and over the years have mastered the art of making Rapé. Kuntanawa Rapé has become a famous brand so to speak highly appreciated by connoisseurs and Snuff aficionados. The Kuntanawa family has a few members that are very knowledgable in medicinal plants from the region and this has led to the amazing variety of Kuntanawa Shamanic Snuffs that are being produced by members of the tribe. For those who want to buy Kuntanawa rapé snuff Sacred Connection offers a wide selection of top quality Kuntanawa Rapés.

Kuntanawa Shamanism